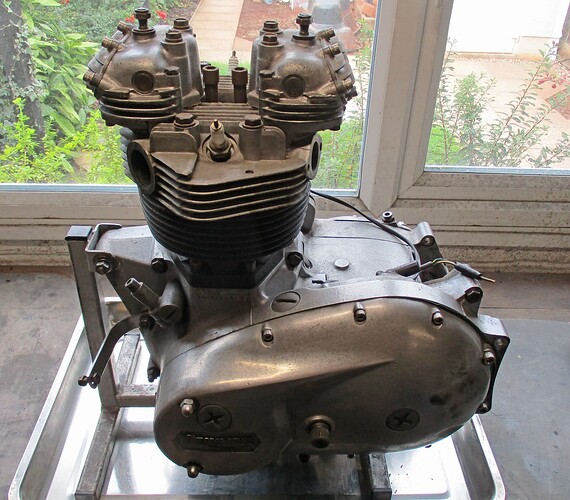

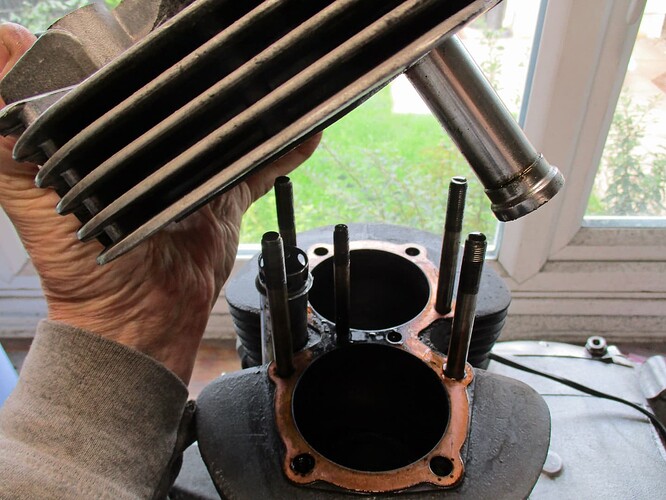

This is a 1978 T140V engine, just removed from a complete bike that is undergoing a bit of a makeover.

These bikes are passing through their 50 years of age. They were the hooligans choice in the 80s as those with deeper pockets moved across to the electric start, faster Kawi Z900s and the hairy two stroke triples with expansion chambers.

The Bonnies left behind were accosted by teenagers with only a hammer and a pair of pliers to keep them going. A lot have been left in a shed or garage for decades. A fair few have been shipped back to their homeland from abroad.

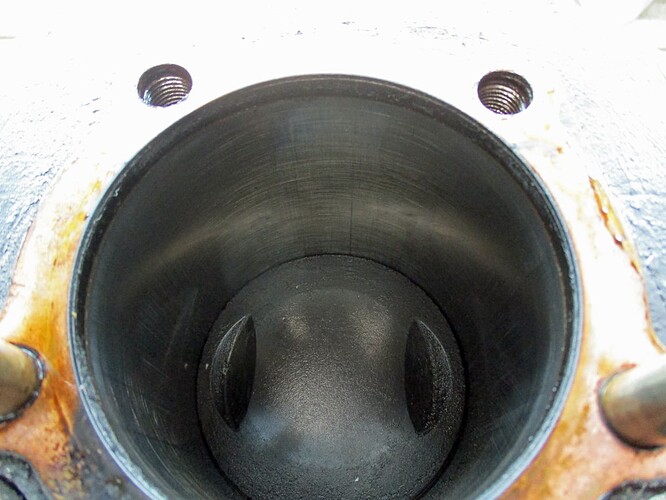

Without knowing the history of the machine, you never know what could be lurking inside. They really need to be stripped down to, at the very least, clean out the sludge trap. (I’ll explain what the sludge trap is later). A blocked sludge trap will ruin your whole day.

Never, ever, believe what a dealer tells you. I’ve bought several from dealers and they have all needed a rebuild.

I’m going to try to show and describe the way through an engine rebuild. I’m no expert at this, I have no expensive machinery or anything other than an ordinary owner’s garage. I have, however, done this a few times before.

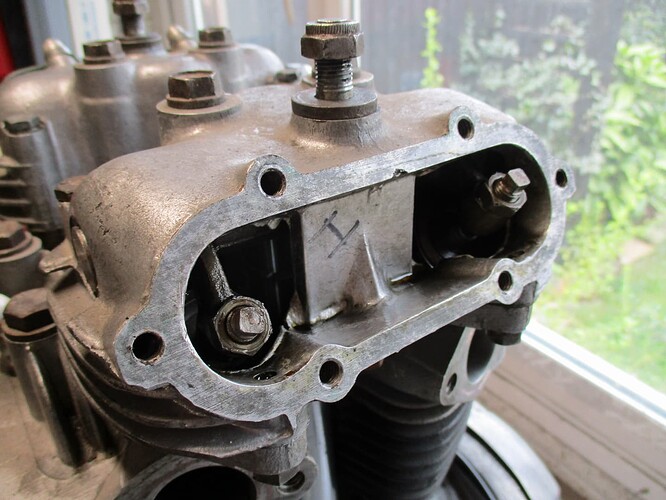

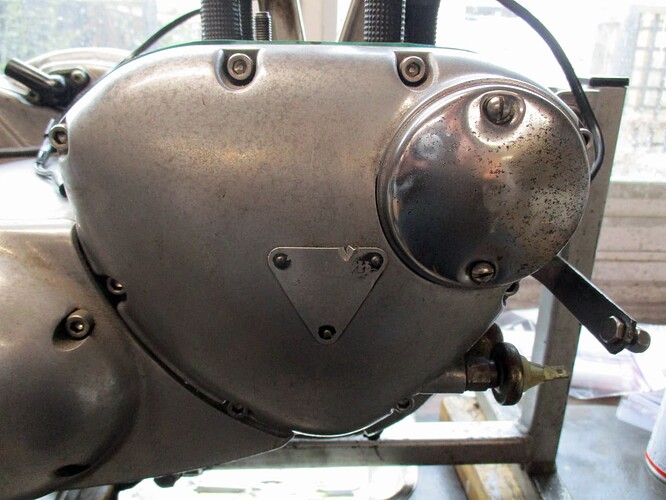

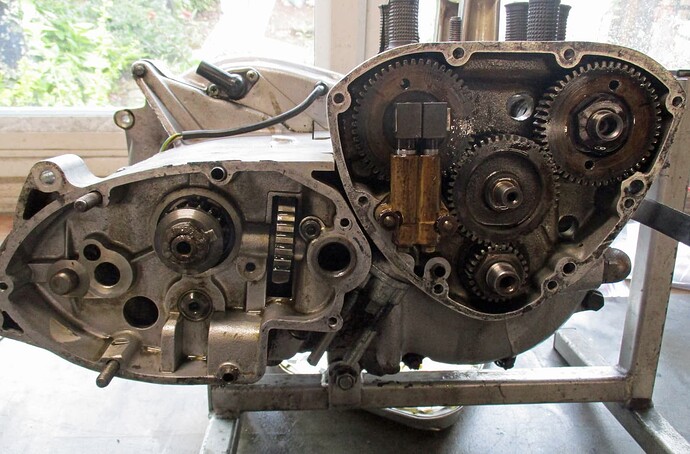

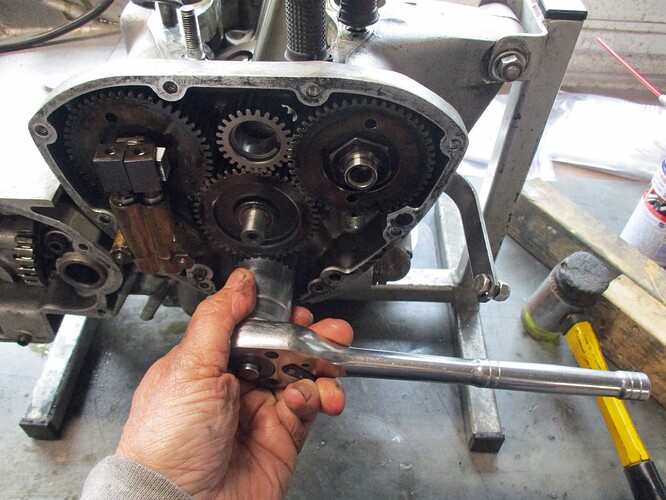

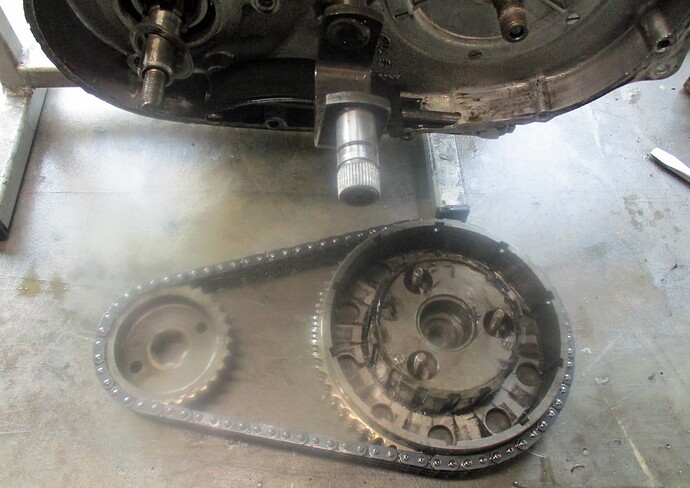

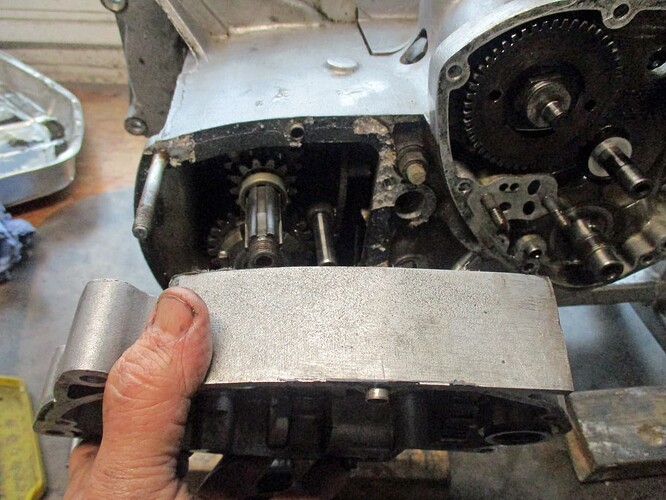

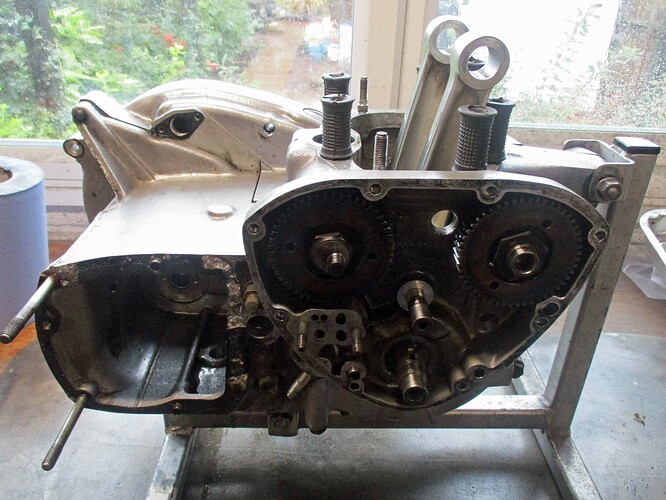

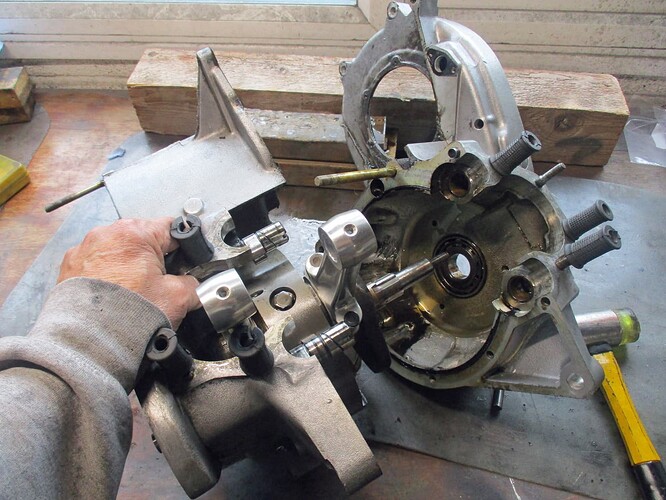

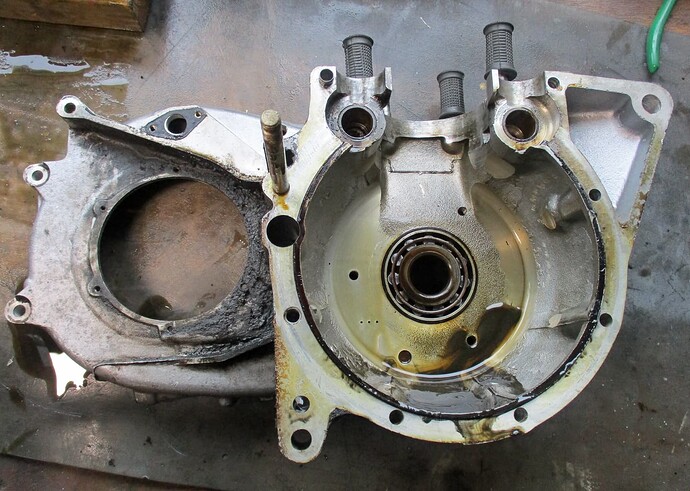

This is the right side of the engine. The facings are as you would sit on the bike. This side is the timing side. The original screws have been replaced by allen bolts so work has been done at some point.

The oval shaped section is the gearbox, the triangular section contains the timing gears with the contact breaker points in the circular cover. (This engine has already been converted to electronic ignition so the points are gone replaced with a Bower Branson system - a pretty simple system to install but we’ll cover that later).

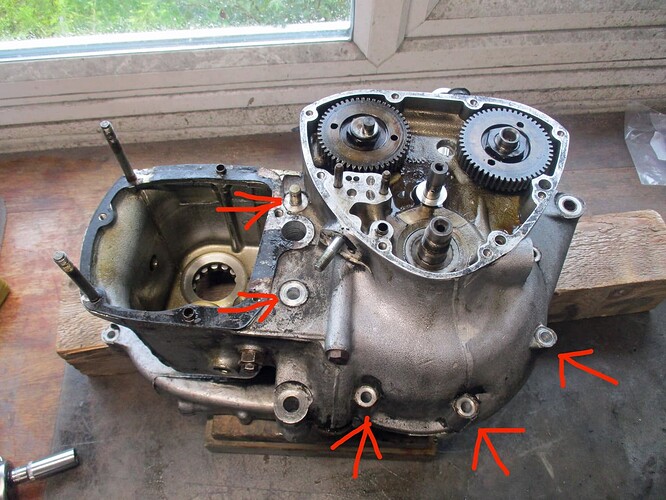

The left side of the engine. This side is the primary side that contains the stator (charging system) and the clutch. This side (after the earlier 70s machines) has the gear change lever. (regulatory right side brake lever for exported models so a change was made). Again, original screws have been replaced with allen bolts.

Just below the barrels the left side casing is stamped with the engine number. When new, both the frame and engine had the same number. Matching numbers are preferred by buyers.

The Triumph Logo was stamped across to deter fakers replicating numbers.

T140V is the type - a Triumph 750cc with 5 gears.

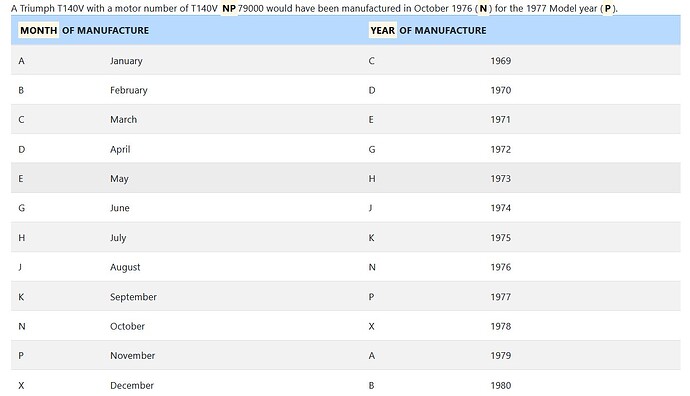

The next two letters G and X are the manufactured date - as shown on here:

G being June and X being 1978.

The remaining numbers are the specific machine off the line.

Sometimes a few more details can be obtained from the Triumph Owners Club (it’ll cost you membership to apply) or the Vintage Owners Club who also have original documents and help with registration numbers etc if you are importing or bringing an unregistered machine back to life

The Vintage Motor Cycle Club - Library and DVLA Forms

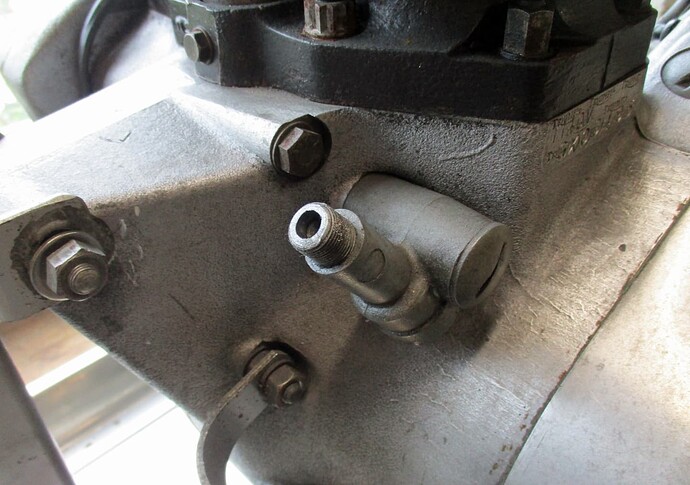

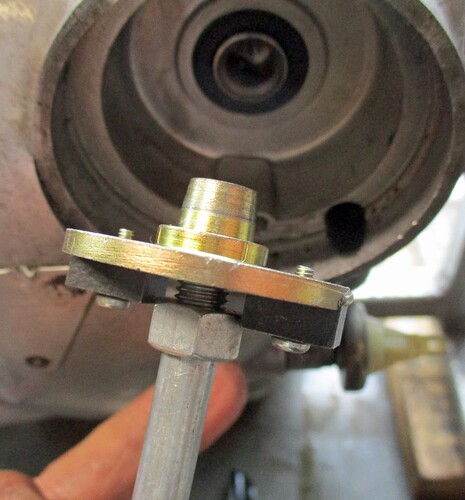

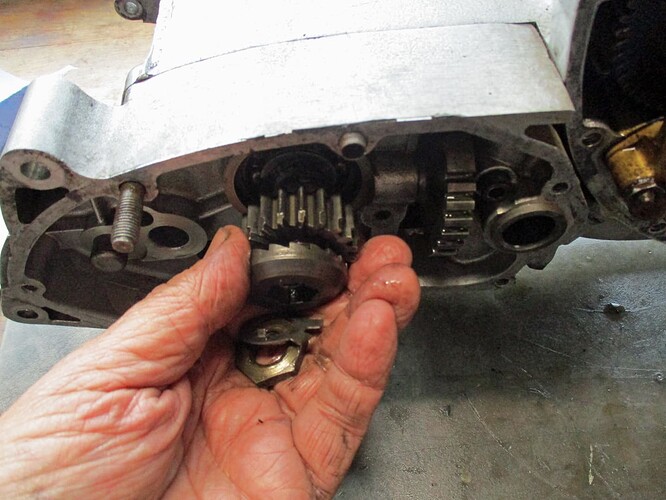

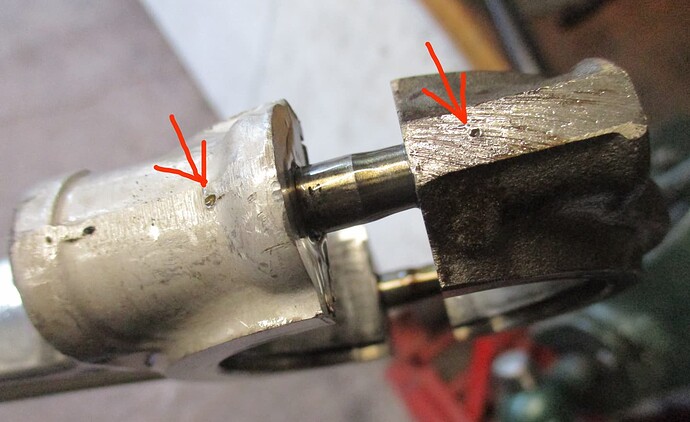

This is the rev counter drive. Sometimes kept, sometimes removed, sometimes left hand thread, sometimes right handed thread. We’ll find out what this one is later.

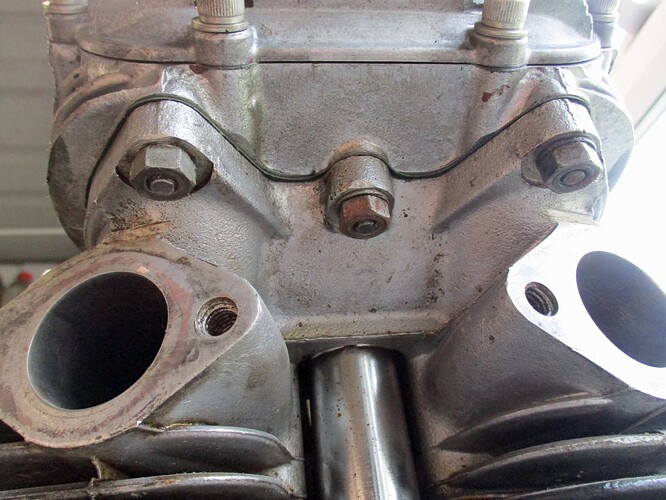

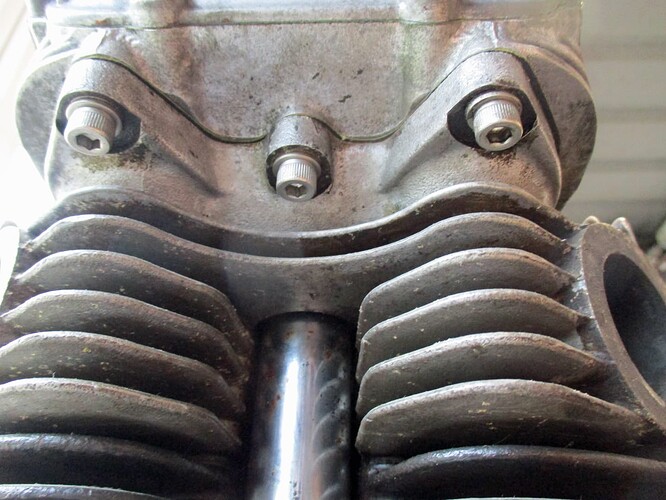

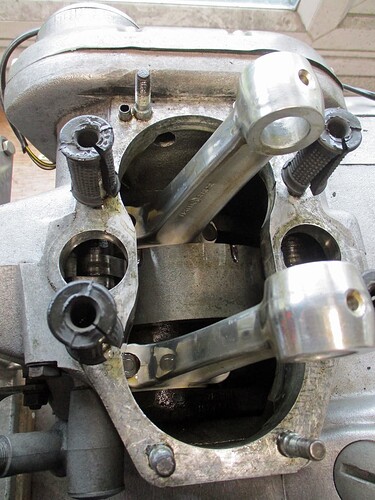

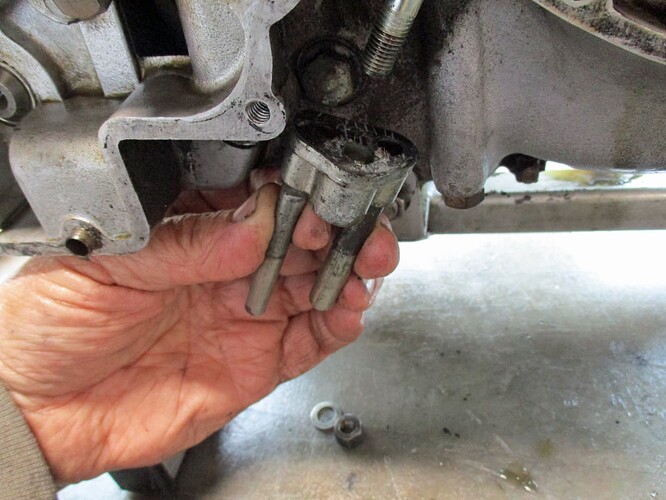

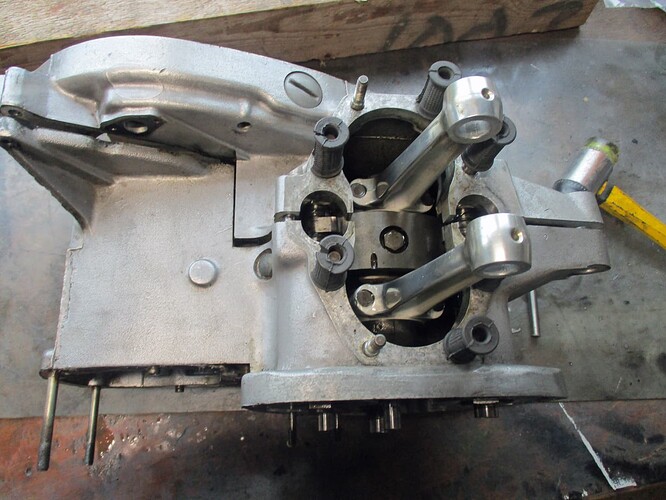

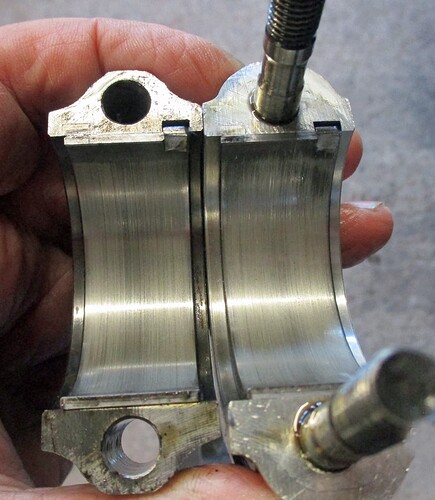

This is view looking up towards the rocker boxes from the inlet side. Note the three nuts. Previous mechanics may have missed these when trying to remove the rocker boxes with a large hammer thinking it is stuck. I’ve seen a few of these welded where they’ve been snapped - check here when buying.

The same view looking up from the exhaust (front) side. The studs and nuts have been replaced with allen bolts. Obviously someone’s been in here but why replace the studs when lost nuts are easily replaced.

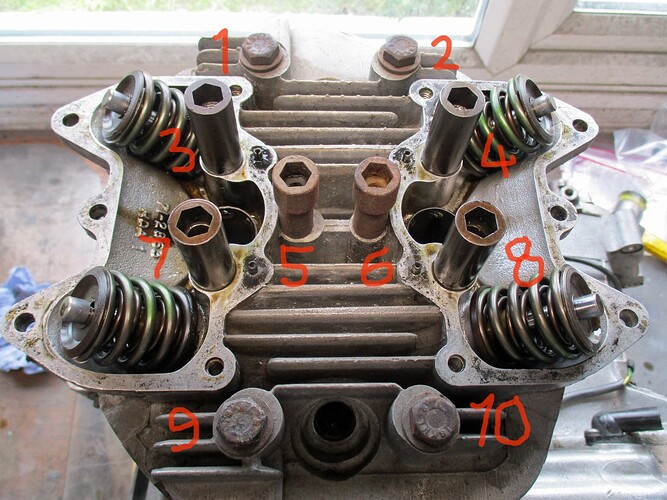

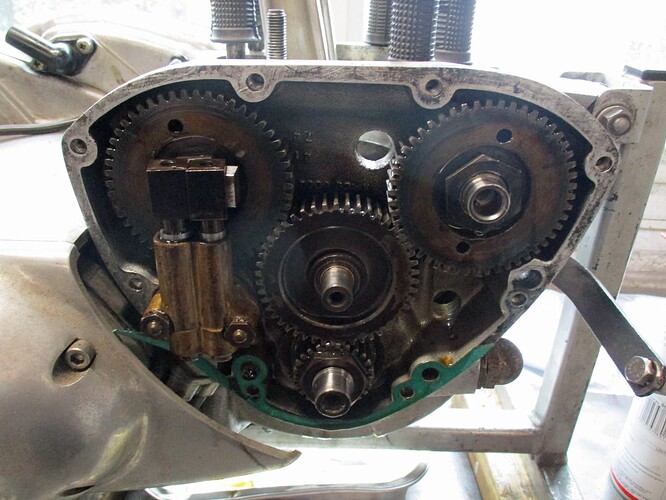

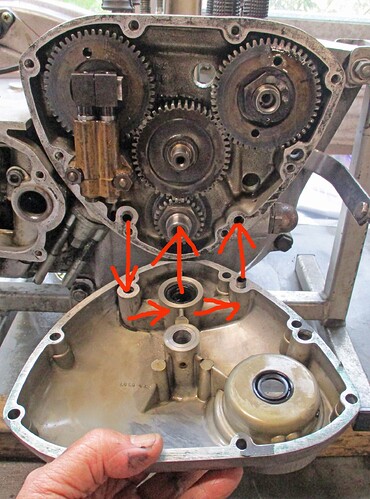

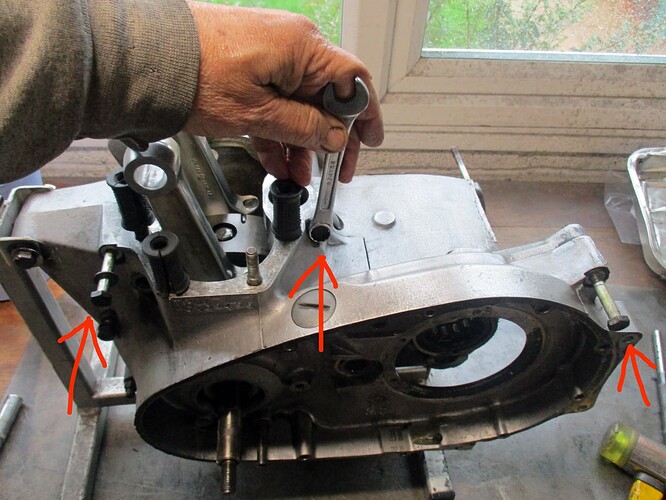

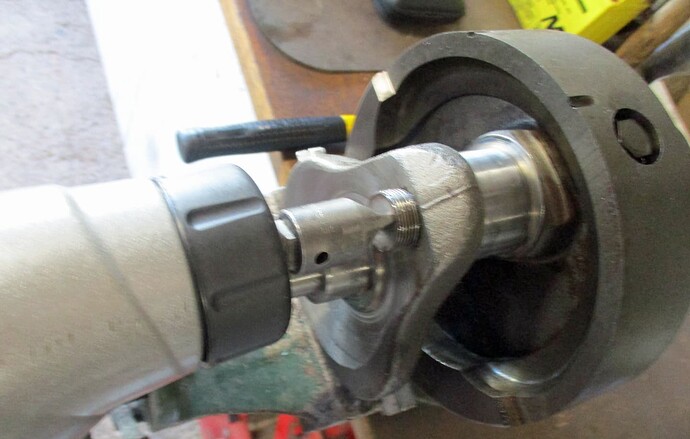

The bottom of the engine. Each casing has a number stamped on the engine mount boss. In this case 331 on both sides which shows that the cases are matching. I’ve had mismatched cases that fit perfectly so if there’s no massive oil leak, why not.

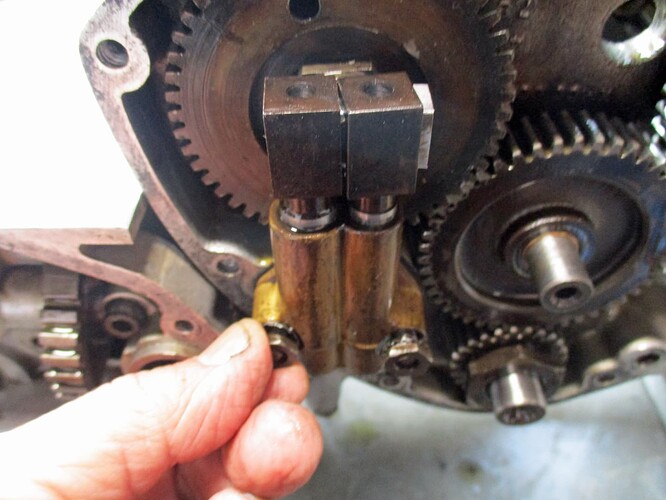

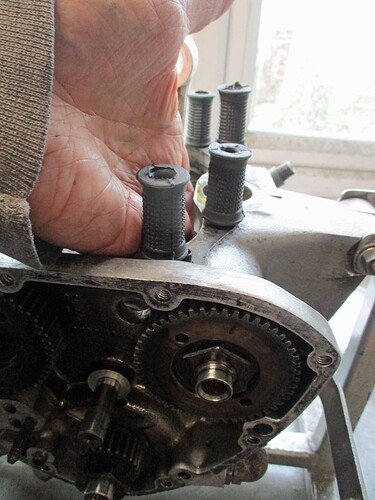

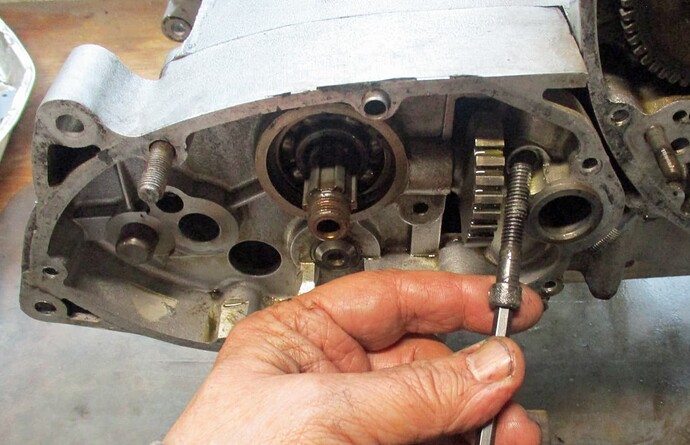

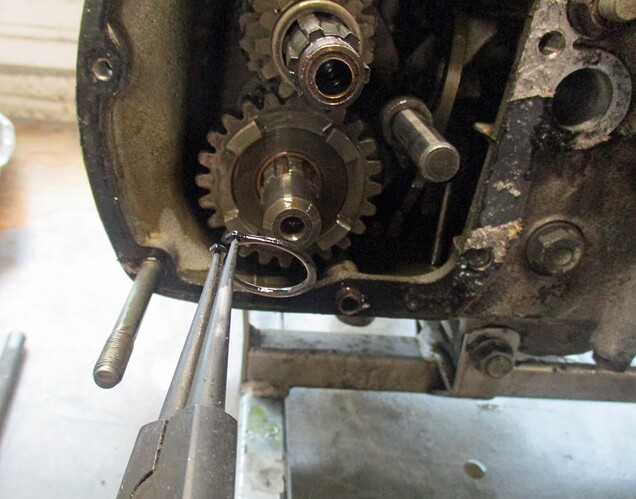

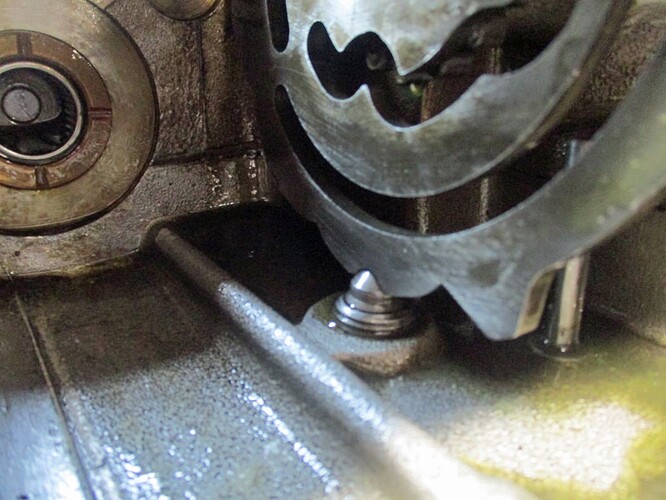

The large deep hex on the left under the gearbox is the housing for the detent plunger that holds the camplate in gear.

The smaller ‘twin’ hex just to the right and up from it, is the gearbox fill level tube and gearbox oil drain bolt.

The large rusty looking hex nut on the other side of the engine mount boss is the sump drain plug.

The smaller hex nut above the drain plug is a drilled oilway plug. This was to allow the engine manufacturers to drill an oilway through to the oil pump, it just stays plugged up with a bolt.

The two rubber hoses above that are the delivery and return hoses to the oil tank.

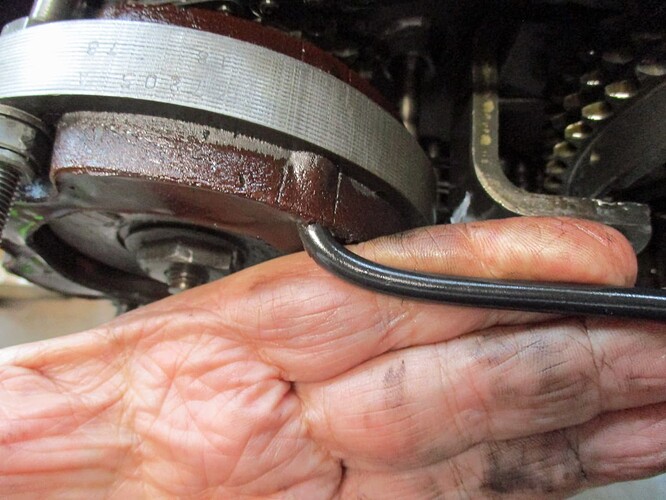

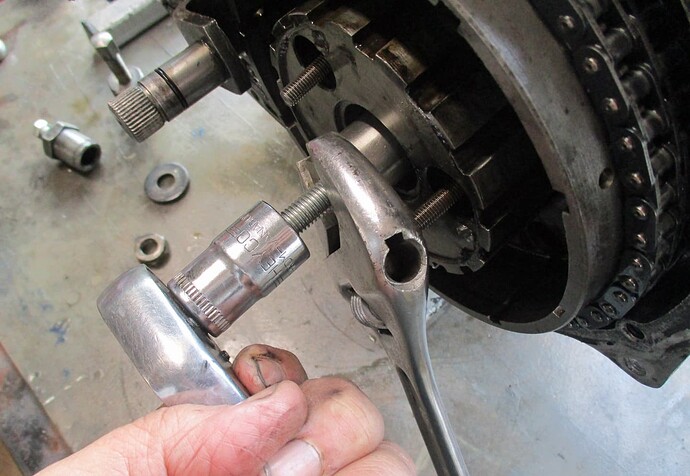

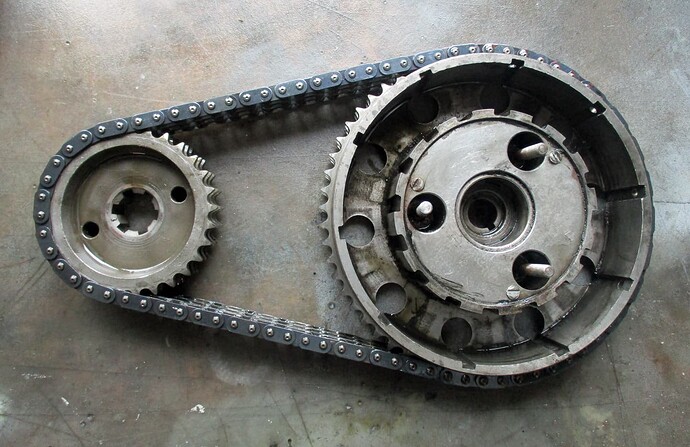

The sprocket seen below the gearbox is the front chain sprocket. It can only be removed with the clutch out.

All the other nuts are casing bolts as the casings are split vertically.

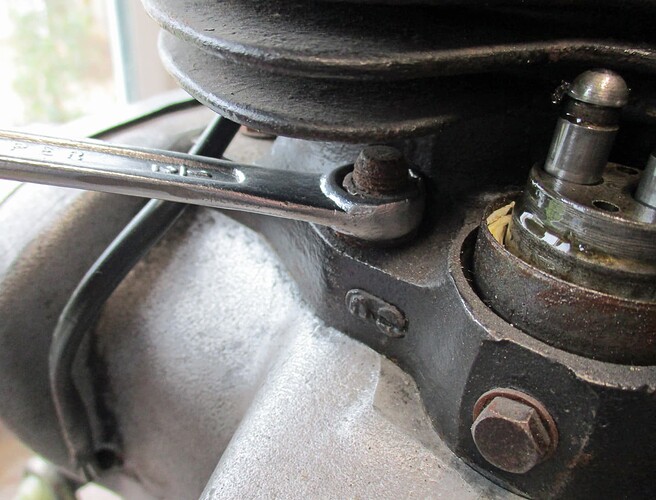

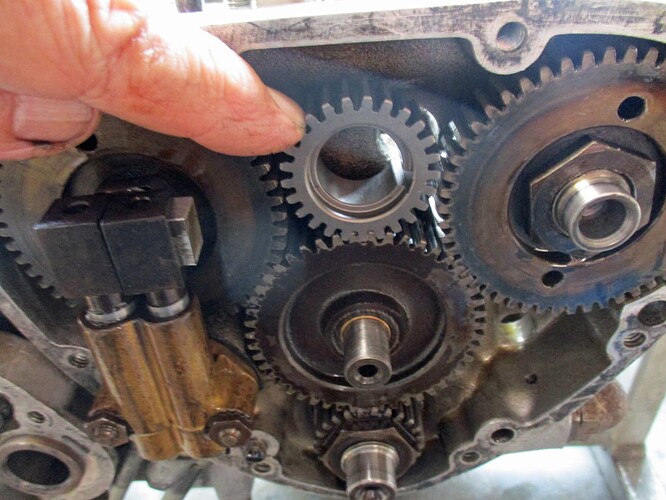

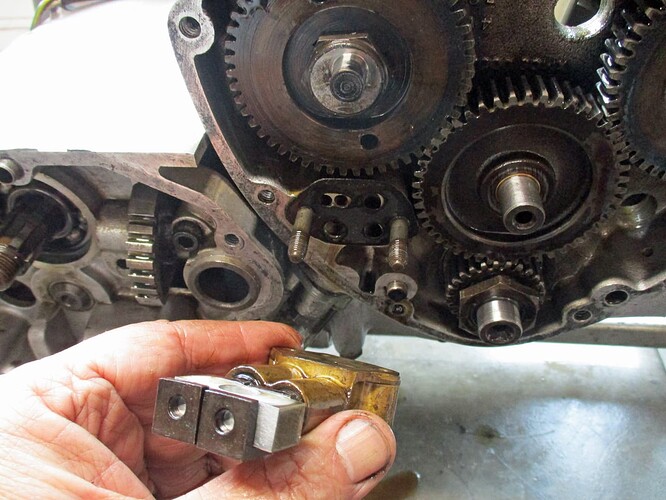

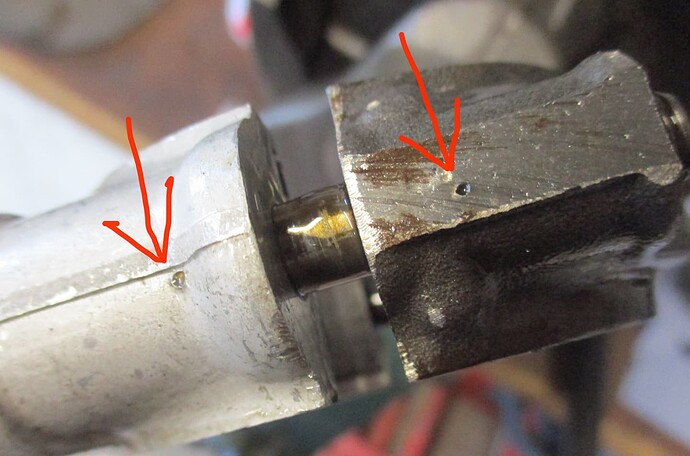

On the front right side of the engine is the oil pressure switch - a simple switch that turns on a light if the oil pressure falls. Some remove this and fit an oil pressure gauge to see the actual readings (I find having a gauge to watch can become a bit obsessive).

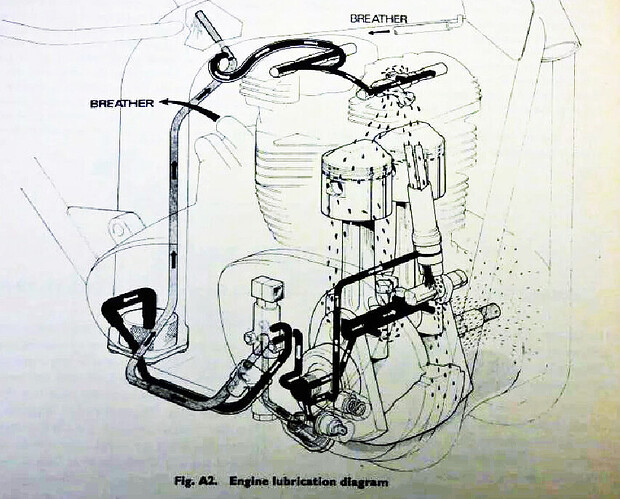

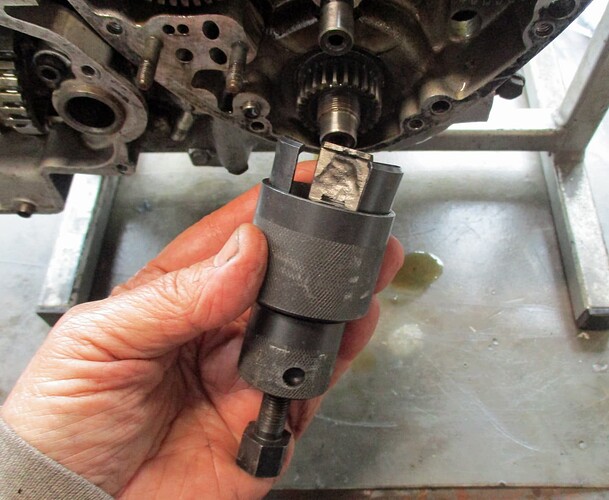

The rusty domed item is the pressure relief valve. This allows any excessive oil pressures to be relieved by allowing oil to pass directly into the sump bypassing the normal route through the crankshaft. This will usually operate when the engine is cold as the oil is generally thicker untill it heats up. I’ll show how it works when it’s dismantled later on.

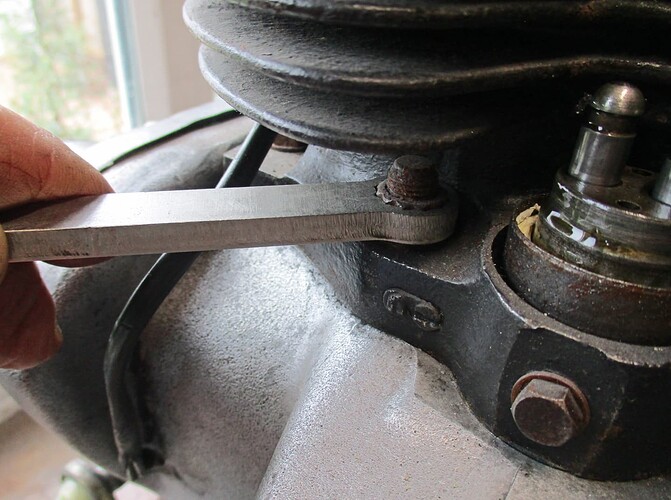

The nut in the centre of the crankcase behind the barrels can be removed to check engine timing. The crankshaft flywheel had two slots cast into it. One for Top Dead Centre and one for 38 Degrees Before Top Deap Centre.

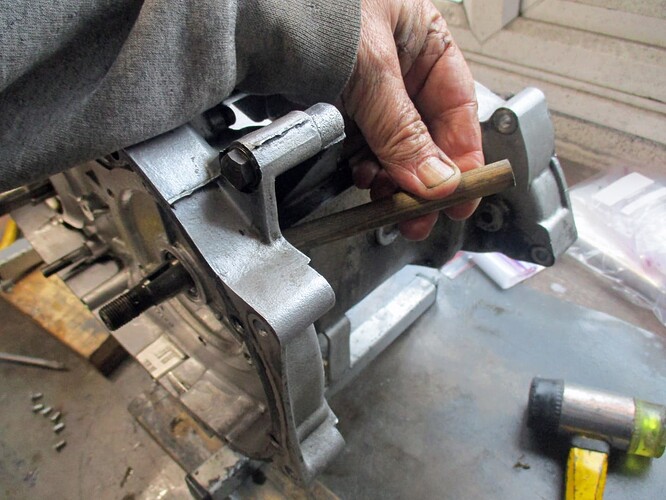

When the nut is removed, a screwdriver - there is a proper tool that screws in but a screwdriver works just as well - can feel and hold the slots while the engine is statically timed.

Talking of proper tools, there are a few special tools that are needed to dismantle and rebuild these engines. They are easily available and not too expensive. They can also be borrowed if you know someone who has a Triumph, but if they are in the toolbox…

Please join in with the thread, add where you can, ask and discuss. These bikes are really cheap at the moment, great fun and it’s better than watching the telly ![]()

Too much talk, I’ll get on with the spanners in part two. ![]() Phew…over

Phew…over